VolgaCTF 2019 - TrustVM

rev- CTF NAME: VolgaCTF 2019

- Category: Reversing

- Files: TrustVM

- Difficulty: Hard

This week-end, to warm up before RuCTF Finals 2019, we playied VolgaCTF and ranked 47 as second italian team. I spent all of my time on this amazing reversing challenge, and we solved it 2 hours before the finish.

~ Intro to the challenge

We were provided of three different files:

- reverse-> a 64 bit executable

- encrypt -> a strange binary file

- data.enc -> An encrypted file, that obviously contains the flag

This executable takes two arguments: “progname” and “filetoprocess”. You can encrypt a file to watch the output. Let’s launch:

./reverse encrypt cleartextfile

on a simple file having 4 ‘a’; the output is a file called “cleartextfile.enc” that contains:

00000000: e924 fb27 bf43 05ee ae0b 1019 f069 a182 .$.'.C.......i..

00000010: 8813 819b 7b5e 2392 d38d 868b dc2b 5ffc ....{^#......+_.

00000020: 2b1e deb0 0015 ce8d 60aa 3386 1d62 55dd +.......`.3..bU.

00000030: 9e8e 28ef 0165 0ae8 86e5 4273 f8ac f265 ..(..e....Bs...e

This is an overview of the main function in IDA:

That’s exactly what I was looking for to pack my bags for Russia !

Let’s start Reversing

In general, this binary is an interpreter of 512 bit code and what is interpreted is the “encrypt’ program, that have encrypted a file called “data”, resulting in the “data.enc” file. In the first part of the binary, the two files, passed as arguments, are read and stored on the heap, and some global variables are initialized. I renamed some of them based on their meaning (or what I think is their meaning)

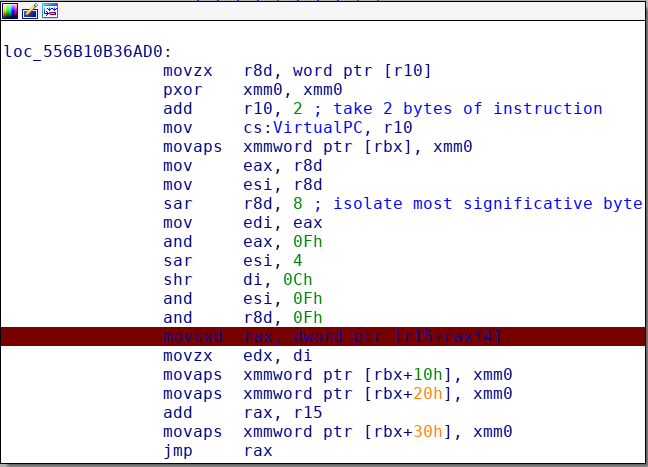

After that, we arrive at this part of the code, where:

- Two bytes from the “encrypt” program are read

- The “Virtual program counter” is incresed of two bytes

- The 4 byte instruction, is separated in 4 parts (nibble) that are stored in various registers, in this way:

Example : instruction bytes -> 0x9fa3

rax -> 9fa3 & 0xf -> 3, is the "instruction number"

rdi -> 9 parameter

rsi -> a parameter

r8 -> f parameter.

Those parameters are used in different ways in each instruction.

Finally there is a switch, to select what function execute, based on the value of rax (instruction number)

I will walk through the most important instructions interpreted by this “Virtual machine”.

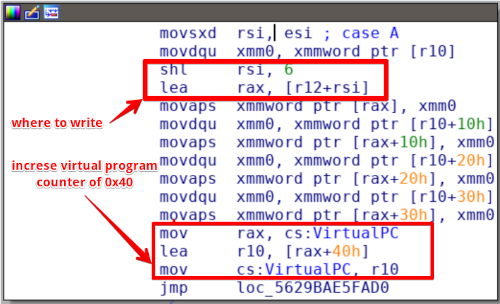

Instruction 0xA ~ Store

This is a basic instruction, used many times by “encrypt” program. It is used to store the next 0x40 bytes of the interpreted program, into the virtual memory of the interpreter, at offset “x”, where “x” is a parameter passed in rsi. All is multiple of 0x40 because it’s a 512 bit program, infact the parameter in rsi is multiplied by 2^6 (shl rsi, 6)!

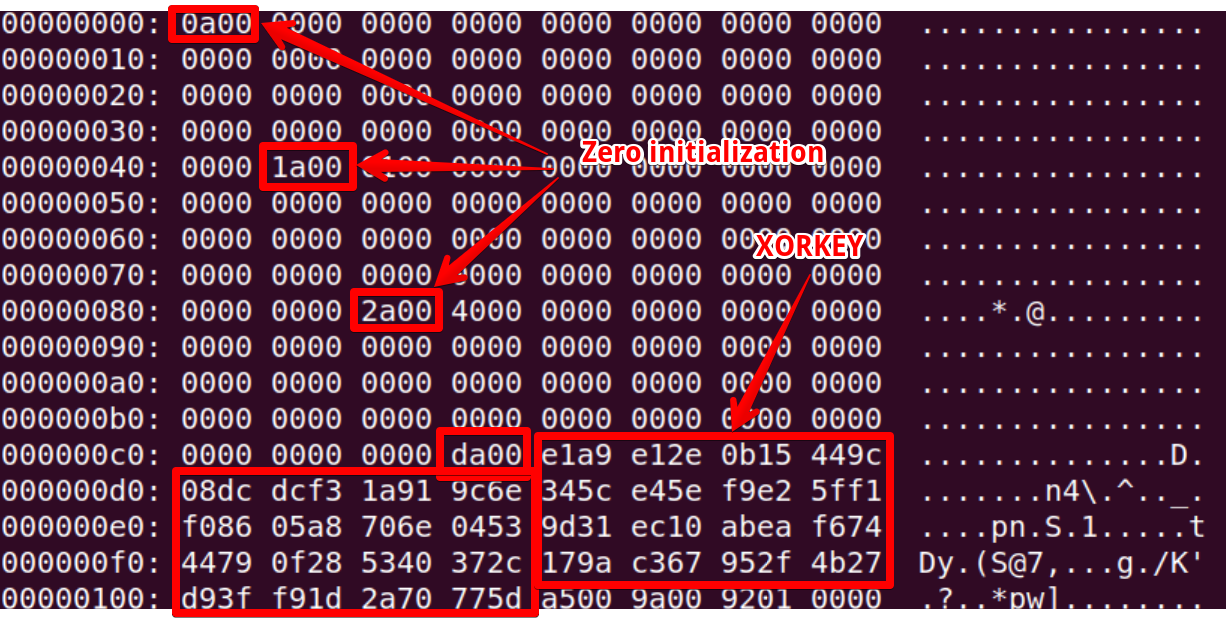

After three 0 initialization of memory, the program do a “0x00dA” instruction, that store a lot of bytes into memory. Those bytes rapresent the initial xor key used to cypher the cleartext passed as argument.

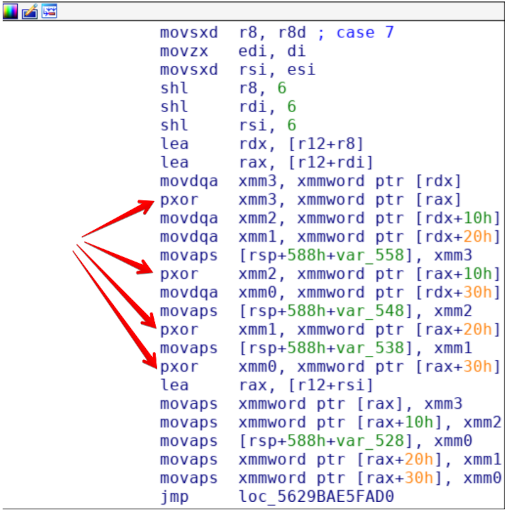

Instruction 0x7 ~ Xor

Instruction 0x7 is used to xor two blocks of 0x40 bytes in memory. At first what is xored, is our first block of cleartext, and the xorkey retrived by the program.

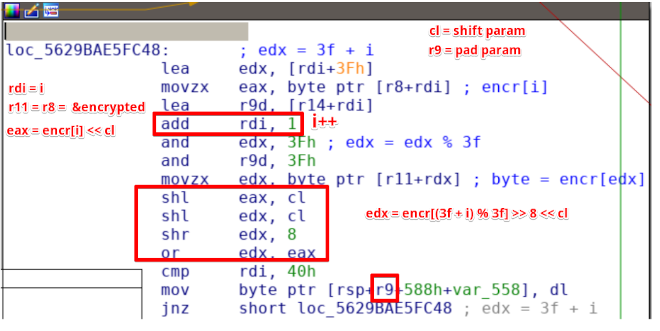

Instruction 0x8 ~ Crypt

This is the most important part of the program, that encrypt a 0x40 block of data, with two parameters, that I will call “shift” and “pad”, which are stored respetively in RCX and R9. The cleartext xored with the initial key, is crypted using 5 and 9 as parameters. After a bit of reversing, I defined the encryption function in python in this way:

def encr(bytes, offset, shift):

newinp = [i for i in range (0, 0x40)]

for i in range (0, 0x40):

eax = ord(bytes[i]) << (8-shift)

edx = ord(bytes[(0x3f + i )% 0x40]) >> shift

newinp[(offset+i) % 0x40] = chr ( ((eax|edx) & 0xff))

return "".join(newinp)

After that, my teammate @zxgio, was able to invert this function, and retrive the function to decrypt the block:

def decr(in_block, offset, shift):

out_block = [0] * BLOCK_SIZE

for i in range(BLOCK_SIZE):

x = ord(in_block[ (offset+i) % BLOCK_SIZE ])

out_block[i] |= x >> (8-shift)

out_block[ (i-1) % 0x40 ] |= (x << shift) & 0xff

for x in out_block: assert 0 <= x <= 255

result = "".join(chr(x) for x in out_block)

return result

Encryption process

If each block had been encrypted with the same parameters and xored with the same key, the game would have finished, but unfortunatly it was more complicated. After a bit of dynamic analysis we understood that the process of encryption was defined like this:

xored1 = xor (cleartext0, xorkey)

first_crypted_block = crypt(xored1, 9, 5)

xorkey = xor (cleartext0, crypt (xorkey, 13, 7))

xored2 = xor (cleartext1, xorkey)

second_crypted_block = crypt(xored2)

...and so on

Then what we have to do to invert this process is:

cleartext0 = xor ( decrypt(first_crypted_block, 9, 5), xorkey)

xorkey = xor (cleartext0, crypt (xorkey, 13, 7))

cleartext1 = xor (decrypt (second_crypted_block, 9, 5), xorkey)

....

You can notice that the xorkey is encrypted with different parameters compared to the cleartext (another problem to figure out that got us crazy)

Conclusion

At the end we ends up with this python script to decrypt the encoded file “data.enc”:

from __future__ import print_function, division, absolute_import

import sys

BLOCK_SIZE = 0x40

xorkey = "".join(chr(x) for x in [0xE1, 0xA9, 0xE1, 0x2E, 0x0B, 0x15, 0x44, 0x9C, 0x08, 0xDC,

0xDC, 0xF3, 0x1A, 0x91, 0x9C, 0x6E, 0x34, 0x5C, 0xE4, 0x5E , 0xF9, 0xE2, 0x5F, 0xF1, 0xF0,

0x86, 0x05, 0xA8, 0x70, 0x6E, 0x04, 0x53, 0x9D, 0x31, 0xEC, 0x10, 0xAB, 0xEA, 0xF6, 0x74 ,

0x44, 0x79, 0x0F, 0x28, 0x53, 0x40, 0x37, 0x2C, 0x17, 0x9A, 0xC3, 0x67, 0x95, 0x2F, 0x4B,

0x27, 0xD9, 0x3F, 0xF9, 0x1D , 0x2A, 0x70, 0x77, 0x5D])

assert len(xorkey) == BLOCK_SIZE

def decr(in_block, offset, shift):

out_block = [0] * BLOCK_SIZE

for i in range(BLOCK_SIZE):

x = ord(in_block[ (offset+i) % BLOCK_SIZE ])

out_block[i] |= x >> (8-shift)

out_block[ (i-1) % 0x40 ] |= (x << shift) & 0xff

for x in out_block: assert 0 <= x <= 255

result = "".join(chr(x) for x in out_block)

return result

def encr(bytes, offset, shift):

newinp = [i for i in range (0, 0x40)]

for i in range (0, 0x40):

eax = ord(bytes[i]) << (8-shift)

edx = ord(bytes[(0x3f + i )% 0x40]) >> shift

newinp[(offset+i) % 0x40] = chr ( ((eax|edx) & 0xff))

return "".join(newinp)

with open('data.enc', 'rb') as inp, open('data.png', 'wb') as out:

while True:

in_block = inp.read(BLOCK_SIZE)

if len(in_block)!=BLOCK_SIZE:

assert len(in_block) == 0

break

new_block = decr(in_block, 9, 3)

new_block = "".join(chr(ord(x1)^ord(x2)) for x1,x2 in zip(xorkey, new_block))

out.write(new_block)

xorkey = encr(xorkey, 13, 1)

xorkey = "".join(chr(ord(x1)^ord(x2)) for x1,x2 in zip(xorkey, new_block))

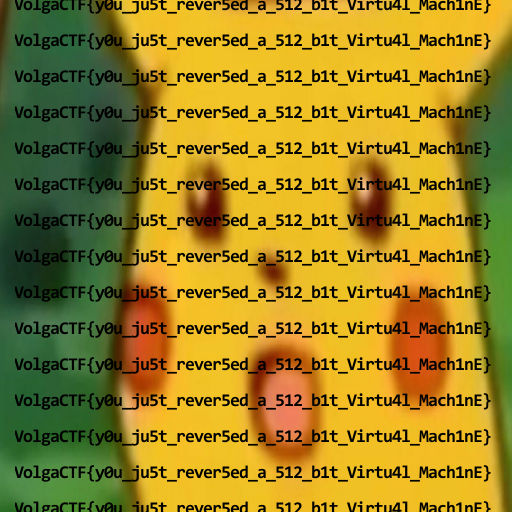

And this is the decrypted file:

Thanks to @zxgio for the great help, it was a great teamwork!

VolgaCTF{y0u_ju5t_rever5ed_a_512_b1t_Virtu4l_Mach1nE}